We now know what opportunity costs are and how that shows us our potential losses based on what could have been. And while that tells us where our money should go, there are still other factors to consider such as Margins and their costs and benefits.

Margins can be thought of as the next unit or a theoretical border. And Marginal Change is basically how change affects this “border” – either positively or negatively. So when weighing up decisions in healthcare, we look at marginal benefits and costs.

Marginal benefits = the benefit of one more unit of output

Marginal costs = the cost of one more unit of output

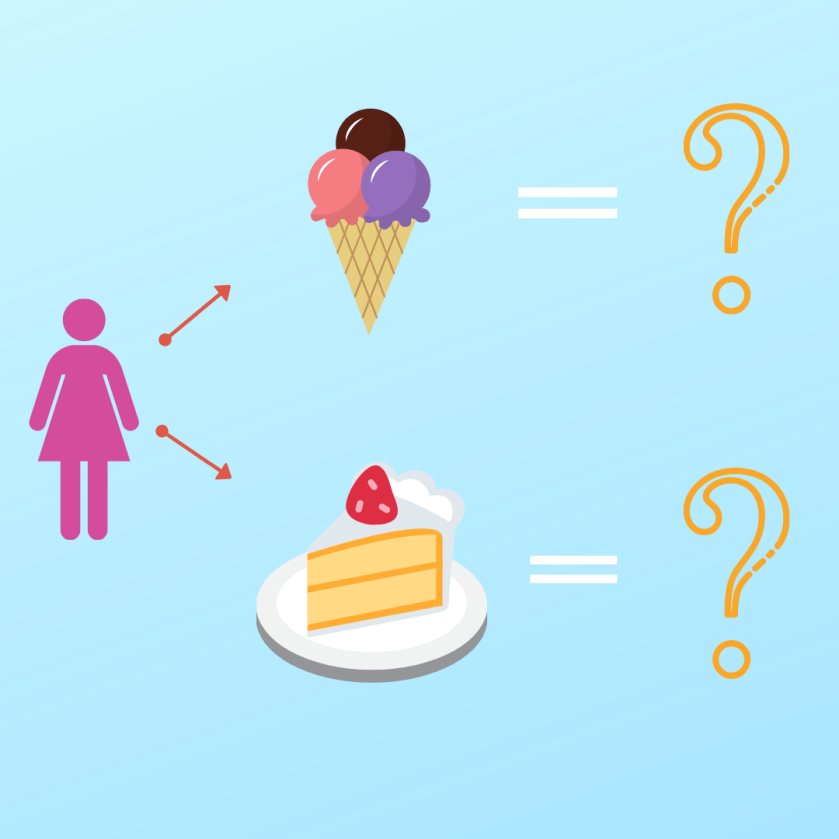

And because I like silly anecdotes to help me remember things. I think of my friend who was very worried about fitting into her wedding dress. So if the marginal benefit of having a slice of cake is greater than the marginal costs, she proceeds to have a slice of cake – cause it is delicious! However, let us pretend that having that one slice of cake will mean she will no longer fit into her wedding dress and she does not have time to get it altered for the wedding. Then we could say here that the marginal costs outweigh the benefit of having that yummy slice of cake, so she decides she is not going to have it – cause although it is yummy, her wedding will be ruined because she won’t have a dress to wear.

What is this I hear about the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility?

I think it is important to note that Utility here refers to satisfaction or happiness gained by the recipient.

That is a pretty interesting phenomenon. You know when you decide to dig into a pint of Ben & Jerry’s and that first mouthful is the best feeling in the world? But then you have more and more, and by the end of it you feel sick cause you are lactose intolerant and realise that it was a terrible idea to eat the whole pint of ice cream. (Or is this just me?) Now that is diminishing marginal utility – cause each extra unit of input yields less and less additional output/benefit. Essentially the benefit or the good diminishes as the consumption of it increases.

So, how does this work in healthcare.

Well marginal analysis – understanding the costs, benefits and diminishing marginal utility help us get the most bang for our buck really. It lets us know how well an intervention/screening programme or service is run as well as if it is worth investing more or further in it.

It also tells us when resources should be moved from programmes producing less

marginal benefit per unit of cost to programmes producing more, as then the total benefit from the resources will increase.

The million dollar question is – Will spending more on healthcare truly show a benefit or are we going to experience the law of diminishing utility, where more money is pumped into healthcare but quality of life and overall satisfaction stagnates. Could the same additional funds instead be allocated to education or housing with better utility?

While I still do not know the answer to that question, I would love to hear your take on it.